Community Supported Agriculture and Its Role in Expanding Food Security

By: Camlyn Takahashi

Community Supported Agriculture’s innovative system for distributing fresh produce directly from farmers to their consumers has implications beyond simply the ease and reliability of having healthy foods in homes. While individuals who pay an upfront fee are ensured access to fresh fruits and vegetables throughout the season, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) has also expanded its impact to disadvantaged communities (Kelley et al., 2014). From the programs enacted that connect CSA to safety net clinics, to educational ones that supply knowledge about food systems to its consumers, Community Supported Agriculture has an immense influence on creating greater access to foods with health benefits, as well as advancing awareness of diet-related issues like obesity (Seguin-Fowler et al., 2016).

Figure 1: This display of food is an example of what a box from CSA might contain. Image from Yasukochi Family Farms.

Diets including healthy servings of fruits and vegetables are associated with a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, obesity, and many other chronic diseases because of the crucial nutrients and bioactive compounds found in them (Boeing et al., 2012). However, regions with lower socioeconomic status have lower concentrations of grocery stores with fruits and vegetables compared to wealthier regions (Seguin et al., 2017). In order to disrupt this prominent inequity, CSA markets directly to neighborhoods rather than through supermarkets. While CSA programs mitigate some of the physical barriers to accessing fresh produce, initiatives to distribute cost-offset CSA (CO-CSA) packages remove the financial burden.

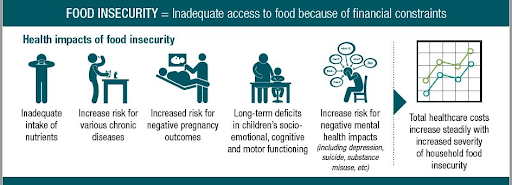

Figure 2: This illustration depicts some of the adverse effects of food insecurity.

Studies have also demonstrated positive results from directly connecting patients of safety-net clinics, which are primary care centers for non-Medicaid insured adults, to CSA plans (Nguyen et al., 2016; Izumi et al., 2020). During a 23-week grant-subsidized CSA program called CSA Partnerships for Health, results were statistically significant for the patients in the categories of increased vegetable intake, eating habits, food security, and general health status (Izumi et al., 2020). Another study that joined federally qualified health center patients with CSA resulted in improved diet quality, with individuals reporting that they had learned “the importance of social support during the program” (Izumi et al., 2018). These successes emphasize the important role Community Supported Agriculture plays in making healthy foods accessible and building support systems.

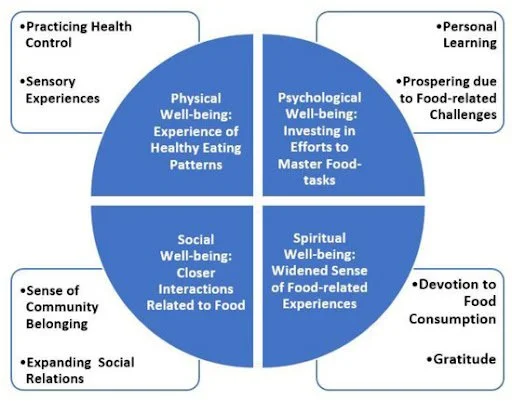

Figure 3: This diagram illustrates the health benefits that result from CSA participation, including mental and physical wellness.

The focus on helping the most vulnerable in modern-day CSA programs has its philosophical roots from the Alternative Food Movement in Japan during the late 1960s and early 1970s. As the country transitioned from subsistence to commercial farming, many citizens became concerned about the synthetic chemicals involved in harvesting their food. They found solutions in the promise of organic farming, which eliminated health risks associated with pesticides (Kondo, 2021). The direct partnership between organic farmers and customers known as the teikei movement promoted goals such as “setting prices in the spirit of mutual benefit” and “emphasizing learning” (Kondoh, 2014). Evidently, Teruo Ichiraku, the founder of teikei, emphasized the social reformation aspect of these alternative food systems as being crucial for their success (Kondoh, 2014).

Concerns in Japan regarding the detriment of small, organic farms due to the spread of industrialized farming were paralleled in the United States, facilitating a similar movement that began with Black farmers. Dr. Booker T. Whatley’s focus on regenerative agriculture that commercial farms disregarded inspired environmentalists including Dr. George Washington Carver, who drew upon his ideas to create “clientele membership clubs” (Espejo, 2022). These clubs allowed members to choose their produce throughout the season after paying an upfront fee (Anstreicher, 2020). These partnerships granted agency for individual food choices, while ensuring business for small farmers.

When considering the benefits of CSA for its participants, the sustainability of its practice must also be addressed. Areas of concern for farmers include the low capital and reliance on volunteers rather than professional workers which may demotivate their employees in the future (Samoggia et al., 2019). Studies have also reported farmers’ concern for the obstacles involved in starting a CSA or CO-CSA program, such as the administrative time required in addition to time cultivating (Pitts et al., 2021). Evidently, the trajectory of CSA’s capabilities is uncertain regarding the navigation of logistics. Despite this, CSA continues to inspire people to learn about habits of healthy eating and practice food cultivation, the spirit promulgated by founders of these businesses that can still be observed today (Birtalan et al., 2020).

References

Anstreicher, K. (2020, July 14). News & notes : Connect. Glynwood. Retrieved January 15, 2023, from https://www.glynwood.org/connect/news.html/article/2020/07/14/the-untold-history-of-csa

Birtalan, I. L., Bartha, A., Neulinger, Á., Bárdos, G., Oláh, A., Rácz, J., & Rigó, A. (2020). Community Supported Agriculture as a driver of food-related well-being. Sustainability, 12(11), 4516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114516

Boeing, H., Bechthold, A., Bub, A., Ellinger, S., Haller, D., Kroke, A., Leschik-Bonnet, E., Müller, M. J., Oberritter, H., Schulze, M., Stehle, P., & Watzl, B. (2012). Critical review: Vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. European Journal of Nutrition, 51(6), 637–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-012-0380-y

Izumi BT, Higgins CE, Baron A, Ness SJ, Allan B, Barth ET, Smith TM, Pranian K, Frank B. Feasibility of Using a Community-Supported Agriculture Program to Increase Access to and Intake of Vegetables among Federally Qualified Health Center Patients. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018 Mar;50(3):289-296.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.09.016. Epub 2017 Nov 22. PMID: 29173943.

Izumi BT, Martin A, Garvin T, Higgins Tejera C, Ness S, Pranian K, Lubowicki L. CSA Partnerships for Health: outcome evaluation results from a subsidized community-supported agriculture program to connect safety-net clinic patients with farms to improve dietary behaviors, food security, and overall health. Transl Behav Med. 2020 Dec 31;10(6):1277-1285. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibaa041. PMID: 33421087.

Kelley, K. M., Kime, L. F., & Harper, J. K. (2014). Community Supported Agriculture (CSA). Penn State Extension. Retrieved January 15, 2023, from https://extension.psu.edu/community-supported-agriculture-csa#section-1

Kondo, C. (2021). Re-energizing Japan's teikei movement: Understanding intergenerational transitions of diverse economies. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 103–121. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2021.104.031

Nguyen OK, Makam AN, Halm EA. National Use of Safety-Net Clinics for Primary Care among Adults with Non-Medicaid Insurance in the United States. PLoS One. 2016 Mar 30;11(3):e0151610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151610. PMID: 27027617; PMCID: PMC4814117.

Jilcott Pitts, S., Volpe, L., Sitaker, M., Belarmino, E., Sealey, A., Wang, W., . . . Seguin-Fowler, R. (2022). Offsetting the cost of community-supported agriculture (CSA) for low-income families: Perceptions and experiences of CSA farmers and members. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 37(3), 206-216. doi:10.1017/S1742170521000466

Samoggia, A., Perazzolo, C., Kocsis, P., & Del Prete, M. (2019). Community Supported Agriculture Farmers’ Perceptions of Management Benefits and Drawbacks. Sustainability, 11(12), 3262. MDPI AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su11123262

Seguin, R. A., Morgan, E. H., Hanson, K. L., Ammerman, A. S., Jilcott Pitts, S. B., Kolodinsky, J., Sitaker, M., Becot, F. A., Connor, L. M., Garner, J. A., & McGuirt, J. T. (2017). Farm Fresh Foods for healthy kids (F3HK): An Innovative Community Supported Agriculture intervention to prevent childhood obesity in low-income families and strengthen local agricultural economies. BMC Public Health, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4202-2

Seguin-Fowler, R. A., Hanson, K. L., Jilcott Pitts, S. B., Kolodinsky, J., Sitaker, M., Ammerman, A. S., Marshall, G. A., Belarmino, E. H., Garner, J. A., & Wang, W. (2021). Community Supported Agriculture Plus Nutrition Education improves skills, self-efficacy, and eating behaviors among low-income caregivers but not their children: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01168-x

Images

(n.d.). Yasukochi Family Farms. Retrieved February 11, 2023, from https://www.yasukochifamilyfarms.com/csa .

Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health. (2018). Health Impacts of Food Insecurity. Food Insecurity Screening. Retrieved February 11, 2023, from https://foodcommunitybenefit.noharm.org/resources/implementation-strategy/food-insecurity-screening.

(2020). MDPI. Retrieved February 11, 2023, from https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/11/4516#.