The Future of Postpartum Depression Treatment

By: Camlyn Takahashi

When considering mothers' health complications during pregnancy and labor, postpartum depression (PPD) is dangerously overlooked. With the pervasive societal problem of shaming new mothers and the unrealistic expectation of only happiness after bringing a newborn home, many women are reluctant to share their feelings of depression. In response to the immense number of undiagnosed postpartum depression cases in recent decades, many individuals have shared their stories to create a more open dialogue (Elliott et al., 2020). However, medical understanding of postpartum depression lacks clarity even with greater awareness surrounding the disorder. PPD has also been treated in the same manner as other mood disorders, such as Major Depressive Disorder, with psychotherapy and antidepressants (Wisner et al., 2002). Yet, the many studies conducted to compare these disorders often highlight differences. Monumentally, the FDA approved the first drug specifically designed to treat postpartum depression in 2019.

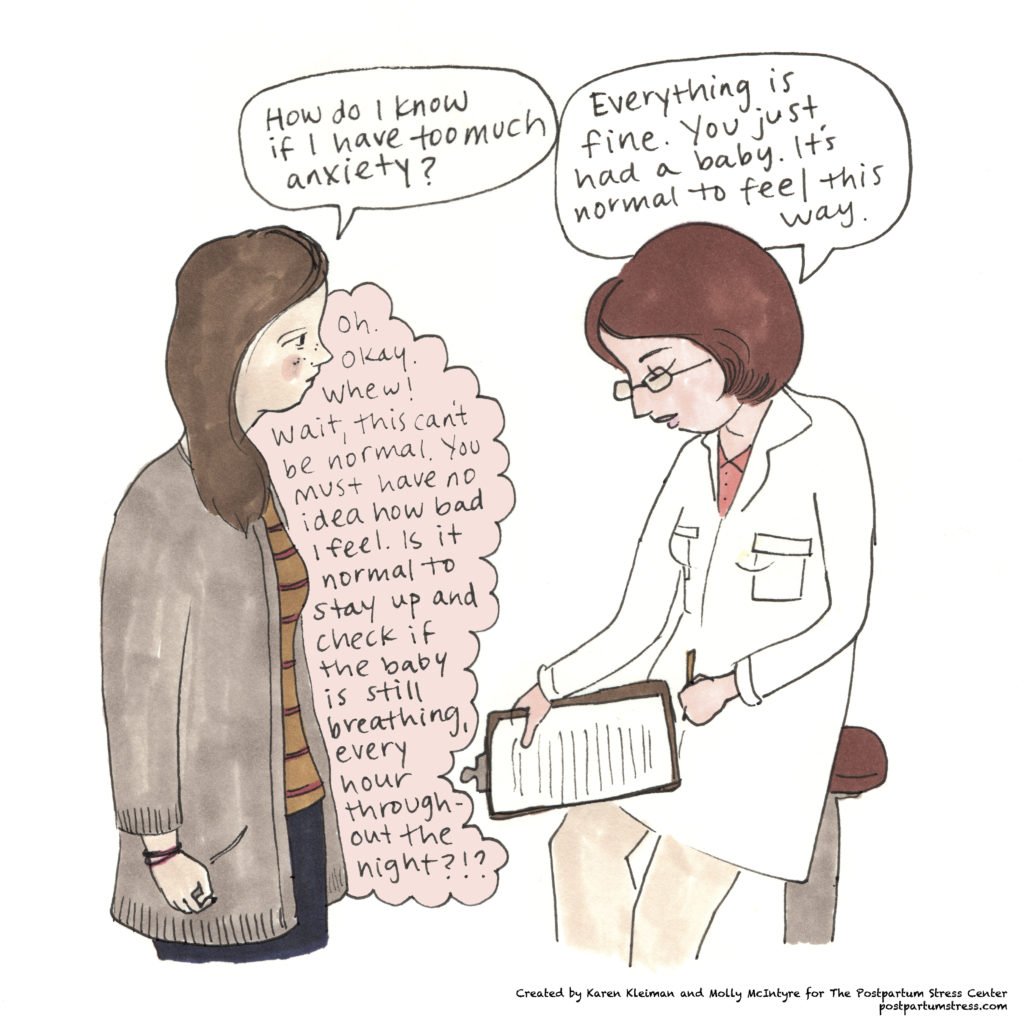

Figure 1.

Illustration of the prevalence of postpartum depression in society and the lack of treatment. Image from Postpartum Depression Facts and Figures 2016.

Launched under the corporation Sage Therapeutics, Brexanolone, sold under the brand name Zulresso, is an innovative drug for new mothers targeting PPD symptoms (U.S Food and Drug Administration, 2019). The Cleveland Clinic summarizes the uniqueness of Zulresso compared to typical antidepressants in the following statement: “This novel therapy, administered around the clock for 60 hours, uses a neurosteroid to control the brain’s response to stress. This treatment design is groundbreaking as it targets the signaling thought to be deficient in hormone-sensitive postpartum depression” (2022). Another improvement of this medication is its timely effect. Typical antidepressants often take weeks to months to begin their impact (Morrison et. al, 2019). The quicker results from Zulresso decrease the risks associated with the delay of certain medications that impact the entire family such as lack of infant and mother bonding, as well as psychological problems of depression or aggression in the partners (Kinsey & Hupcey, 2013; Roberts et al., 2006).

In addition to being a scientific breakthrough for treatment, the invention of Zulresso is important when considering the stigma and lack of knowledge surrounding postpartum depression. Around half the cases of PPD go undiagnosed because of apprehension for mothers to honestly report their symptoms with fear of facing judgment (Mughal, 2022).

Figure 2. This illustration was created by advocates for postpartum depression awareness, depicting the anxiety many experience.

The differences in how patients are screened for PPD also contribute to the disparities in diagnosis. Symptoms resulting from a disrupted sleep cycle, changes in appetite, and the challenges of taking care of a newborn limit healthcare providers from determining depression as opposed to the results of a new environment (Kettunen et. al, 2014). The hindrance in testing is evident as the most commonly used test to diagnose PPD given self-reported symptoms, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) “has lower sensitivity and specificity for detecting a major depressive episode in the postnatal period (variably defined) than a major depressive episode occurring at other times” (Jolley, 2007).

The EPDS is less adept at measuring a depressive episode for those experiencing PPD, resulting in the fact that women in perinatal groups are less likely than those not pregnant to receive a diagnosis of depression both during pregnancy and postpartum (Geier et al., 2014).

Patients with postpartum depression have unique symptoms including increased anxiety, instability, and hyperarousal. Additionally, PPD has a higher rate of heritability: 54% compared to 32%. Yet, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which guides healthcare professionals in assessing mental disorders in the United States, classifies Postpartum Depression as a subtype of Major Depressive Disorder, with the distinction of PPD being that it occurs “with peripartum onset” (C.T. Beck & Indman, 2005; Viktorin et al., 2016; American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Following Zulresso’s success in reducing depressive symptoms, Sage Therapeutics is in the process of conducting trials of an oral pill, which will make the drug more accessible compared to the intravenous administration (Gabryel, 2022). This innovation is the beginning of positive results from the momentum created by advocates for understanding the chemical nature of this disorder and validating the necessary support for mothers (Elliott et al., 2020). As more options for women post-birth become available, society can hopefully move past the days of undermining women’s suffering and embrace effective solutions.

References

Beck, C. T. (2006). Postpartum depression. AJN, American Journal of Nursing, 106(5), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000446-200605000-00020

Belluck, P. (2019, March 19). F.D.A. approves first drug for postpartum depression. The New York Times. Retrieved October 6, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/19/health/postpartum-depression-drug.html

Bicking Kinsey, C., & Hupcey, J. E. (2013, December). State of the science of maternal-infant bonding: A principle-based concept analysis. Midwifery. Retrieved October 6, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3838467/

CBS Publishers & Distributors, Pvt. Ltd. (2017). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: Dsm-5.

Elliott, G. K., Millard, C., & Sabroe, I. (2020). The utilization of cultural movements to overcome stigma in narrative of postnatal depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.532600

Gabryel, C. (2022, June 8). Phase 3 skylark study of Zuranolone in postpartum depression met its primary and all key secondary endpoints. Newsroom. Retrieved October 6, 2022, from https://news.unchealthcare.org/2022/06/sage-therapeutics-and-biogen-announce-the-phase-3-skylark-study-of-zuranolone-in-postpartum-depression-met-its-primary-and-all-key-secondary-endpoints/

Geier, M. L., Hills, N., Gonzales, M., Tum, K., & Finley, P. R. (2014). Detection and treatment rates for perinatal depression in a state Medicaid population. CNS Spectrums, 20(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1092852914000510

Hamilton, J. A. (1992). 2. the issue of unique qualities. Postpartum Psychiatric Illness, 15–32. https://doi.org/10.9783/9781512802085-008

Jolley, S. N., & Betrus, P. (2007). Comparing postpartum depression and major depressive disorder: Issues in assessment. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 28(7), 765–780. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840701413590

Kettunen, P., Koistinen, E., & Hintikka, J. (2014). Is postpartum depression a homogenous disorder: Time of onset, severity, symptoms and hopelessness in relation to the course of depression. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-014-0402-2

Morrison, K. E., Cole, A. B., Thompson, S. M., & Bale, T. L. (2019). Brexanolone for the treatment of patients with postpartum depression. Drugs of Today, 55(9), 537. https://doi.org/10.1358/dot.2019.55.9.3040864

Mughal S, Azhar Y, Siddiqui W. Postpartum Depression. [Updated 2022 Jul 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519070/

Roberts, S. L., Roberts, S. L., Bushnell, J. A., Roberts, S. L., Bushnell, J. A., Collings, S. C., & Purdie, G. L. (2006). Psychological health of men with partners who have post-partum depression. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(8), 704–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01871.x

Top 10 for 2022. Cleveland Clinic Innovations - Top 10 Medical Inventions | Cleveland Clinic Innovations. (2022, February). Retrieved October 2, 2022, from https://innovations.clevelandclinic.org/Programs/Top-10-Medical-Innovations/Top-10-for-2022

Viktorin, A., Meltzer-Brody, S., Kuja-Halkola, R., Sullivan, P. F., Landén, M., Lichtenstein, P., & Magnusson, P. K. E. (2016). Heritability of perinatal depression and genetic overlap with Nonperinatal Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(2), 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15010085

Image References

Postpartum Depression Facts and Figures. (2016). Fix. Retrieved October 6, 2022, from Source: Fix.com Blog.

Postpartum Depression – signs and treatment. Geisinger. (n.d.). Retrieved March 22, 2023, from https://www.geisinger.org/patient-care/conditions-treatments-specialty/post-partum-depression

Kleiman, K. (2019). Mom and Doctor Conversation Postpartum. The Postpartum Stress Center. Retrieved October 6, 2022, from https://postpartumstress.com/get-help-2/are-you-having-scary-thoughts/praise-for-good-moms-have-scary-thoughts/.